One of the criticisms I often hear of high-end bike companies is that all of their frames are made in Taiwan (or, increasingly, China). The assumption here is that production costs in developing countries are so low that brands are outsourcing to drive up their profits and make more money–and that’s usually a pretty good assumption. But as a guy trying to get a prototype frame built, so far it’s been my impression that Taiwan is not the cheapest, but rather the only place to do it.

I hope I’ll be proven wrong, but so far companies in Taiwan, and their trading agents, have proven to be drastically more responsive and interested in building the frame. Stateside builders I’ve talked with either lack resources and need a year or more to get something built, or don’t seem interested in getting back to me. And that sucks. I’d rather build this prototype here. In an ideal world, I’d even like to have options in a fabricator, and get this single frame built in six months.

But what’s become pretty obvious to me is that there’s just not much small-scale manufacturing going on here. That isn’t to say we can’t make things. In a backyard DIY sort of way, we’re still the top of the food chain. We still have enough of a middle class that once upon a time had disposable income for some of us to have small machine shops and painting booths in our garages, and we know how to genuinely create something. But we seem to go straight from “I have a friend who can MIG weld” to “Alcoa,” without all that much in between.

No, we’re more of a “Service Economy,” which means we better hope they keep opening new Starbucks.

At least BikeRumour was showing off some serious hardware that’s U.S. made.

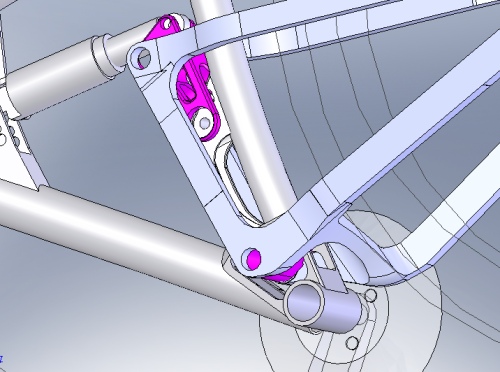

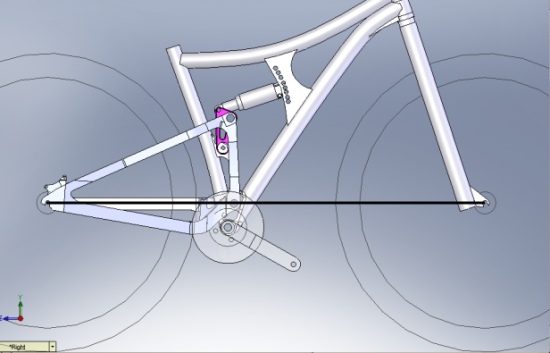

Speaking of the prototype I’ve looking to create, most of the questions I’ve been getting revolve around (pun intended) the lower rocker. Here’s a detail shot:

One of the patented aspects of the design is the position of that lower rocker. Unlike a lot of short lower rocker orientations, this design lets the swingarm attach at the front of the rocker–ahead of where the rocker attaches to the frame. This allows for several things I believe to be very good, but one key characteristic of the design is a 29’er-friendly axle path.

Most people can understand that the larger diameter rear wheel causes clearance issues with the frame–in particular, once a bump force acts on the suspension and moves the rear wheel upward, it doesn’t take long for that arcing big wheel to get really close to the bike’s seat tube. That part’s pretty straightforward. But a 29er’s bottom bracket also sits lower relative to a bike with 26″ wheels. Because of that lower bottom bracket (aka “increased bottom bracket drop”), a totally unladen 29er is a little like a 26″ wheeled bike that’s already partway into its rear travel.

This all means that axle path relative to that bottom bracket shell is critical on a 29er. (In the process of working this out, I looked at Niner’s CVA system, which is a pretty brilliant way to deal with the challenges of the added bottom bracket drop on a 29er.) Getting sufficient travel without having to shove the seat tube forward (shortening the effective length of the rider’s compartment) or pushing wheel out behind the rider with longer chainstays (which can decrease maneuverability and make the bike ride “flat footed”), is a challenge.

After a whole lot of hours testing rocker widths, angles, and orientations, I believe I’ve found an axle path that will let a 29er be as agile as most 26″ wheeled bikes. There was also a very specific effect I wanted to see happen with the swingarm, and I’ll have some more on that later.